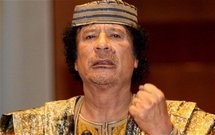

Tripoli has emerged since the fall of former Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi's regime in 2011 as a weaker national capital, though this is not necessarily a problem for Libya's future as a parliamentary democracy. Because Libya's geographic divisions make it difficult for a central government to impose its will throughout the country by any means other than brute force, a decentralized government may be the more appropriate model for long-term political stability.

Tripoli has emerged since the fall of former Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi's regime in 2011 as a weaker national capital, though this is not necessarily a problem for Libya's future as a parliamentary democracy. Because Libya's geographic divisions make it difficult for a central government to impose its will throughout the country by any means other than brute force, a decentralized government may be the more appropriate model for long-term political stability.

However, the process by which Libya has moved from Gadhafi's dictatorship to less centralized control has been fraught with security lapses and violence caused by various militant groups, which appears likely to continue in the near term. Still, Tripoli will likely conclude that the risks from exerting too little central control are outweighed by the risks from inviting a regional backlash and sparking another civil war by exerting too much.

Almost half of Libya's population lives in Tripoli and Benghazi or their surrounding areas. Gadhafi's regime was based in Tripoli, which is much closer to Tunisia and the Maghreb than Benghazi in Libya's east. A desert separates the two cities and makes up the majority of Libyan territory. The distance and geographic barrier between the two coastal cities allowed different regional identities to emerge in the centuries before Libya's modern borders were drawn, and these differences are at the center of the country's governance challenges.

Libya's modern boundaries were established in 1934 when it became an Italian colony after Rome took control of Tripoli and Benghazi from the Ottomans in the early 20th century. The Italians divided Libya into the western, eastern and southern administrative regions that exist today. Libya then came under British control in 1943 until declaring independence as the Kingdom of Libya in 1951. During all these periods, the powers ruling Libya understood the need to balance between the competing centers of power in Tripoli and Benghazi; although Libyan King Idris hailed from Cyrenaica, he too alternated capitals between Tripoli and Benghazi to prevent a rival power base from emerging in the other city. Gadhafi's regime, founded in 1969, represented the alternative way of ruling Libya's vast and disparate desert territory: using a strong central government and authoritarian control to suppress Libya's strong regional identities.

Tripoli's Political Evolution

After Gadhafi's ouster in October 2011, Libyans for the first time had the opportunity to craft a political system representative of their interests instead of an imposed system of political control. Libya's ongoing political evolution represents a logical return to a system prioritizing local identities and politics over the dictates from a distant government in Tripoli. Because of this weakening of the central government, wide swathes in the center of the country are not controlled by either Tripoli or Benghazi, a situation militant groups have been able to exploit.

Tripoli is reluctant to impose too heavy a central government presence in regions with strong local representation, such as the militia-backed local councils of Misurata and Benghazi. Similarly, even regional power centers such as Benghazi are unable to effectively police their surrounding areas and cooperate with Tripoli to patrol borders and maintain national security. The result has been continuation of a diverse group of local militia councils, armed with weapons plundered from Gadhafi's abundant weapons caches during the revolution.

These revolutionary councils frequently overlap with Libya's complex tribal and ethnic social structures, compounding the geographic challenges facing any central government seeking to rule Libya. And given the manner in which Libya ousted Gadhafi, these revolutionary militias and local councils see themselves as defenders of the revolution, making it critical for Tripoli to deal with these groups with respect, even deference, in order to maintain open channels for dialogue and possible cooperation.

Libya's Emerging Balance of Power

Tripoli's political transition is increasingly viewed with apprehension by many of the Western forces that intervened during the Libyan revolution, especially in light of the ongoing French intervention in Mali. Recent statements from British, French and EU officials reflect the growing fear that Libya and its substantial exports of light, sweet crude oil could again fall to civil war. The killing of U.S. Ambassador to Libya Christopher Stevens in September 2012 and the historic prevalence of Islamist militants in eastern Libya have only added to concerns that the country is on the brink of descending into greater instability and becoming as a fractured warlord state along the lines of Afghanistan after the Soviet pullout in 1989.

However, Tripoli has a significant advantage over Afghanistan in preventing the devolution into civil war: oil. The country's crude reserves and revenues give the government a tool by which it can incentivize local militias, revolutionary councils, armed groups and even Islamist brigades against taking actions contrary to the government's interests. Oil revenues have been systemically distributed through complex social spending programs and direct cash payments to regional leaders and militias. Tripoli has also created umbrella organizations aimed at protecting energy infrastructure by giving militia groups a share of the oil revenue in exchange for organizing under the leadership of the Interior and Defense ministries.

Beginning with the unelected National Transitional Council, these direct cash payments to the population have been largely successful in preventing violent attacks against both government institutions and on energy infrastructure. Instead, we have seen an increase in largely peaceful demonstrations, either near the General National Congress' headquarters in Tripoli or at oil export terminals and refineries. Local tribal leaders and militias also have an incentive to protect their own regional energy infrastructure from militants and rival groups in the region, which in part led to Libya's relatively quick return to oil production and sustained exports. While regional centers such as Benghazi and Misurata may not wish to cede further authority to Tripoli, they have shown the desire in working together to safeguard mutual interests.

Long-Term Security Challenges

Until local and regional organizations are prepared and willing to take on much of the security burden that heretofore had been the responsibility of the central government, Libya will face a persistent security threat. The apparent assassination campaign in Benghazi against intelligence officials from Tripoli and former Gadhafi regime officials is only one such danger. And as evidenced by Mali, loose government control over a vast desert territory in North Africa can prove to be an attractive breeding ground for militancy.

Feb. 17 will mark the two-year anniversary of the initial uprisings in eastern Libya that eventually toppled Gadhafi's regime. Tripoli has increased its security presence and Western governments have issued security warnings in light of indications that militant attacks against government installations and foreigners could accompany the protests planned to express popular frustration with slow-moving political reforms.

Currently, the biggest potential threat to Libya's stability would be an attempt by the central government in Tripoli to codify far-reaching powers for itself in the still unfinished constitution, reawakening widespread fears about the return of an oppressive security state. Such a move would likely trigger violent, armed opposition to the central government's attempted power grab, leading to a weak central government having to face a number of well-armed regional militias -- similar to the Libyan revolution that toppled Gadhafi himself.

It is too early to determine whether the Libyan government will succeed in striking the right balance between central authority and regional autonomy. Authorities in Tripoli are carefully working through regional concerns and testing its boundaries in the unfamiliar environment of representative government. The ongoing peaceful protests and appeals to the central government from regional power centers reflect a desire by many Libyans to find a stable working relationship that protects regional interests while preventing the rise of another Gadhafi-style ruler.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)