Japan's newest aid and investment in Africa suggests it is redoubling its focus on South and East African nations that border the Indian Ocean. In these countries, it not only runs trade surpluses and sees signs of new resources coming to market but also sees its private companies getting more heavily involved in manufacturing and construction.

Japan's newest aid and investment in Africa suggests it is redoubling its focus on South and East African nations that border the Indian Ocean. In these countries, it not only runs trade surpluses and sees signs of new resources coming to market but also sees its private companies getting more heavily involved in manufacturing and construction.

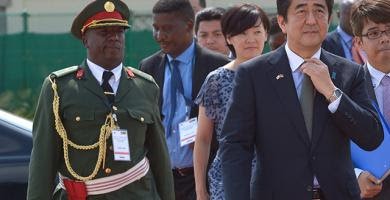

Japan is intensifying its focus on Sub-Saharan Africa. In February, the Japanese Foreign Ministry will release a white paper on official development assistance that will outline Tokyo's plan to devote more funds to African natural resources and growth. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe started off 2014 with a visit to Ivory Coast, Mozambique and Ethiopia, where he promised aid and investment for security, energy and infrastructure. This trip followed his administration's pledge of $32 billion in new aid, investment and loans for 2013-2017 -- well above the $9 billion in aid and the decrease in direct investment stock between 2008 and 2012.

Of these newly pledged funds, 44 percent ($14 billion) will go toward development aid, 20 percent toward financing infrastructure for trade corridors, 6 percent toward natural resource extraction and 6 percent toward low-carbon energy projects. In the past, Tokyo has often exceeded its African investment pledges, but now it faces a challenge to live up to this ambitious target. While global media have characterized Japan's efforts as a challenge to China's expansive presence across Africa, a close look at Japan's latest moves shows an independent strategy concentrated on its national interests.

Japan's Investment Strategy

Japan's pledge comes as the country's inherent resource insecurities and newest economic growth challenges have become more urgent after the 2011 disasters and nuclear shutdown. The government has launched a comprehensive effort to rejuvenate its economy and rebuild its international standing, including its outward investment strategy. Meanwhile, Africa's developing economies face higher uncertainty over foreign investment, especially for export-dependent commodity producers. The world is coming down from several years of relatively synchronized stimulus efforts following the global financial crisis, and commodity demand from China is slowing. From the point of view of African states looking to attract foreign funds, Japan's renewed aid and investment provides timely support.

A long-range strategy is apparent from Japan's use of development aid through state entities like the Japan International Cooperation Agency. The largest portion of the new money going to Africa will come in the form of aid. Tokyo has a history of offering aid, debt forgiveness, famine relief and humanitarian assistance to Africa not only to improve Tokyo's image but also to improve the stability of countries that provide Japan with natural resources, export markets and investment income. Between 1973 and 2013, Japan has given nominally about $18 billion in aid to African countries, according to the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Historically, the aid was split rather evenly between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. Japan has multiple reasons for maintaining involvement in both of these sub-regions. However, the pattern of Japan's donations has changed since the global financial crisis. Not only has the aid come in bursts rather than a steady stream, but since 2008, Japan has shifted the bulk of its aid away from North Africa toward nine Sub-Saharan states, most of which are located in eastern and southern Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique, Zambia, Botswana, Mauritius, Cameroon and Cape Verde. Kenya and Tanzania have always been among the top beneficiaries, but in the past five years Kenya has received nearly half of the aid -- well above its historical average -- and Tanzania's share has grown considerably. Uganda and Mozambique have seen a much greater share of aid in the past five years than their historical average, as has Mauritius.

South Africa has long been Japan's major investment destination in Africa, and this relationship remains central, but Japan is working on expanding connections to nearby Botswana and Zambia with aid. By contrast, in West Africa traditional focal points like Ghana and Nigeria have dropped off, and only Cameroon and Cape Verde received significant aid after 2008 (though Abe's trip marked a resumption of aid to Ivory Coast).

These trends underscore Japan's growing concentration on vibrant economic pockets and emerging extractive industries in eastern and southern Africa and the Indian Ocean basin, where maritime connections and access to the interior have piqued foreign interest. Clearly, one of the reasons Japan invests in the eastern states is to get access to natural resources: Entirely aside from its dominant partner South Africa, it imports copper and cobalt from Zambia and from the Democratic Republic of Congo via Tanzania; diamonds from Botswana; and coal, titanium and soon natural gas from Mozambique.

However, while these states provide critical commodities in growing volumes, that is not their sole importance to Japan. Japan gets most of its African oil and natural gas from the Maghreb and Western and Southwestern African states like Nigeria and Angola, and most of its ores and metals from South Africa and others. The East African states serve as notable export markets -- they are generally net importers of Japanese goods, primarily cars, trucks and buses (it is convenient for Japan to sell vehicles to most of these countries, often secondhand, because they also have the steering column on the right side in order to drive on the left side of the road). They also import machinery such as steel products, steam turbines, forklifts and bulldozers for fast-growing and newly urbanizing areas. Indeed, Kenya, the biggest trading partner of the group, mainly sends fresh-cut flowers, coffee and tea to Japan (as does Uganda), not industrial commodities. While Japan normally runs annual trade deficits with Africa as a whole because of its resource focus, the trade surpluses with the nine countries where it has concentrated recent aid, when combined, have offset an average of one quarter of that deficit over the past 10 years. And the aid itself typically costs less than 1 percent of the surpluses with each country.

Tokyo's Priorities in Africa

The sectors Japan has been targeting also reflect a shift in its strategic aims in Africa. Before Japan's 1990 financial crisis, development aid consisted overwhelmingly of commodity loans, but since then Tokyo has increased the already substantial shares going to transport and telecommunication, while surging aid for electricity and natural gas and building a respectable presence in irrigation, flood control and a range of social services. Increasingly Japan has focused on building African "human security" and social development, with projects in health, water, sanitation and education. Since 2009, commodity loans have plummeted in frequency, while financing for transportation, electric power and gas, irrigation and flood control have surged. These sectors reflect Japan's interest in building steadier and more sustainable consumer bases and transport corridors that are less vulnerable to disruption from power shortages, poor public services and inadequate road and rail.

Despite these aims to lay the foundation for new industrial economies, the interest in resources remains inseparable from the eastern, central and southern African states. This is not only because of these countries' own resources but also because of the access they provide to the interior, where more resources can be exploited. Japanese construction firms get contracts to process resources or bring them to port, and these infrastructure projects aim to build up the stability and vitality of a number of transport and logistics corridors that seek to merge critical African ports with their adjacent interior regions. Most involve building, expanding or rehabilitating roads in countries such as Morocco, Cameroon, Ghana, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar and Zambia, railways in countries such as Malawi, and ports in countries such as Angola, Namibia, Djibouti and Mozambique. The clear emphasis is on linking landlocked states like Zambia, Malawi, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and areas like the mineral-rich southern and eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to ports. The eastern ports range from Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, to Durban, South Africa, and the western ports in Angola and Namibia take advantage of the Trans-Caprivi, Trans-Kalahari and Lobito corridors.

Looking beyond resources and infrastructure, Japan's recent private investments in Africa suggest a growing interest in manufacturing and services. South Africa historically has taken up a large share of Japan's African investment, currently one-third of the total. This status continues, most recently including Nippon Telegraph and Telephone's $3.2 billion acquisition of Dimension Data, which gives the Japanese firm access to African and Middle Eastern markets in telecommunications and a springboard into other services. But recently Japanese companies have been diversifying. While Japan already has a range of factories in South Africa, Tokyo has been putting money into making cars and car parts in Kenya, Nigeria and North Africa; electronics and food processing in Nigeria; furniture, paper and textiles in Tanzania; and into the aforementioned mining in Mozambique, Madagascar, Botswana and Zambia. East African states account for about one-fifth of the major private business deals over the past decade by value -- excluding South Africa, they account for the majority. Tokyo also claims new funds will go toward public-private partnerships that encourage African ownership in private ventures.

Mozambique as a Case Study

Mozambique exemplifies Japan's intensifying Sub-Saharan African focus. Offshore natural gas development of the Rovuma-1 field off the coast of northern Mozambique gives Japan the ability to benefit from a big future exporter of liquefied natural gas. This project will help to increase supply and push down prices at a time when Japan's uncertain nuclear future makes cost-effective liquefied natural gas sources all the more imperative. (Japan's Mitsui Group has a 20 percent equity stake in this project.) Mozambique also has three ports connecting to different inland regions: Nacala, Beira and Maputo. Japan is providing $700 million to develop the Nacala port near the Rovuma field and the railway to central Mozambique's coal fields via Malawi, where, incidentally, Japan hopes to mine rare earths. Penta-Ocean Construction Co. is set to begin the first phase of renovations in Nacala in March. Meanwhile Brazil's Vale is leading development efforts in central Mozambique to produce coal that is to be transported by rail to Nacala for export to international markets like Japan.

Japan is teaming with Brazil to boost commercial agriculture in the Nacala region to provide greater economic and social foundations to an area of subsistence farmers -- an area where the Mozambique opposition party, the Mozambican National Resistance, commonly referred to as Renamo, is campaigning against government neglect of its region. Elsewhere, Japan is boosting electricity generation to improve the reliability of industry in Maputo, where Mitsubishi has long had a hand in the Mozal aluminum smelter. Nippon Steel is developing Mozambique coking coal, and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. has paved the way for financial access to Mozambique via its partnership with South Africa's Absa Bank.

Japan is betting that various investments like these can stabilize Mozambique, where remaining tensions from the 1970s-80s civil war still erupt into violence, and thus create a more reliable energy source and a logistics hub linking Africa's interior to Indian Ocean trade routes and Japan. Mozambique's national elections are set to be held in the fourth quarter, and for the first time since democratic elections were held, Renamo will be a factor -- at the very least by disrupting stability and security. Japan's investments throughout Mozambique will help to foster positive relations with Mozambique's historic political parties and possibly minimize the chance of Tokyo's interests being caught in the middle of a grassroots insurgency and struggle between the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front and Renamo.

The Broader Context for Japan's Investments

Japan maintains its traditional interest in importing energy from North Africa, Nigeria and Angola, a range of other commodities from all across the continent and making deep and diversified investments in South Africa. But East Africa marks the area of rapidly increasing and forward-looking interest.

Japan's various interests in different pockets of Africa also point to another component of its international posture that is changing: the renewed efforts toward military normalization that will heighten the Maritime Self-Defense Forces' presence in the Indian Ocean basin to secure supply lines to and from these countries.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)