West African prospects for electricity production are shaped in large part by Nigeria's potential to develop fossil fuels. Because it holds Africa's greatest volume of oil and natural gas reserves within its borders, Nigeria has optimal access to natural gas. These reserves could be used for electricity production assuming Abuja is able maintain security and political control of the resources.

West African prospects for electricity production are shaped in large part by Nigeria's potential to develop fossil fuels. Because it holds Africa's greatest volume of oil and natural gas reserves within its borders, Nigeria has optimal access to natural gas. These reserves could be used for electricity production assuming Abuja is able maintain security and political control of the resources.

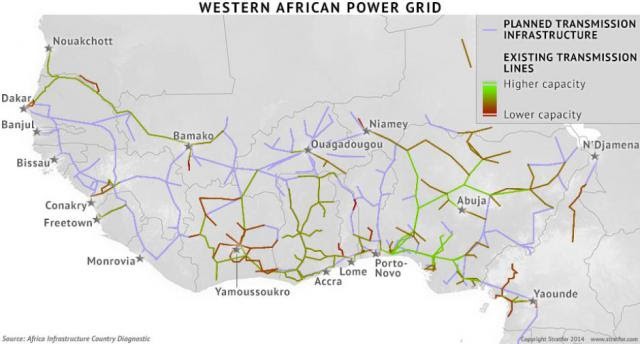

As a result, regional connections between national power grids have spread west and inland from Nigeria. The main cluster is based around the Coastal Transmission Backbone running through Benin, Togo and Ghana and eventually reaching Ivory Coast along the Gulf of Guinea. While some inland connections link Burkina Faso and Niger to this transmission backbone, connectivity with the rest of West Africa is still in the earliest stages of development. Eventually the network could reach as far west as Senegal.

Under the leadership of President Goodluck Jonathan, Abuja aims to at least triple domestic power output and expand the transmission grid throughout the country. However, political wrangling in Nigeria has limited the expansion of domestic electricity generation, and power generation in the country still falls short of demand, resulting in load shedding and blackouts. Nigeria recently privatized the Power Holding Company of Nigeria, hoping the move would generate greater investment in infrastructure development and, as a result, increase domestic power production. Facing its own shortfalls, Nigeria is not able to translate its large natural gas-fired electricity production base into a regional abundance of electricity, leaving much of West Africa to rely on fuel oils for electricity generation.

As development moves forward, increasing transmission capabilities will likely be the main focus when securing investment and building infrastructure. Countries will also seek to increase their own power generation capacity, and ongoing privatization efforts may lead to higher cost efficiency over time. Apart from Nigeria, other countries in West Africa will also push to develop their offshore oil and natural gas deposits. This will lead to some of the natural gas being fed back inland for power generation. West Africa is probably still far from having an effective, regionwide electricity trading pool, and serious infrastructure challenges will need to be resolved before a physical transmission grid could enable the development of trading mechanisms.

The East African electricity transmission network is perhaps the most fragmented in all of sub-Saharan Africa. While there is some interconnectivity among the countries straddling Lake Victoria, the limited capacity of these connections limits power transfers. The lack of connections between Sudan and Ethiopia, and between Ethiopia and Kenya, leaves significant gaps among the main electricity producers in the Eastern Africa Power Pool. The Eastern Africa Power Pool technically extends into North Africa, including Libya and Egypt. But this link exists only on paper for now; no transmission infrastructure actually connects Libya and Egypt to the rest of the Eastern Africa Power Pool.

Connecting the Grids

The focus of the Eastern Africa Power Pool is still very much on expanding the transmission infrastructure connecting national grids, and efforts to that end have moved rapidly since the pool's creation in 2005. The group plans to have a Day-Ahead Market operational by 2017. At that point, work on transmission infrastructure is scheduled to have evolved far enough to at least connect all the countries in the Eastern Africa Power Pool, including Egypt and Libya. Egypt's participation would considerably increase the electricity production capacity of the power pool. Projects to construct transmission infrastructure are slated for completion in 2016, but most of these are still undergoing feasibility studies and remain rather unrealistic in the short term. Pending investment and timely completion of construction, the lack of connections between the grids could limit the Eastern Africa Power Pool's effectiveness to the countries around Lake Victoria.

Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda currently conduct most of the power trading in East Africa. This trade has steadily risen, and as Kenya, the largest electricity producer of the three countries, increases its exports to Tanzania and Uganda, its imports from both countries also continue to grow. Industrial demand and rural electrification in Kenya are raising the pressure on regional production capacity and on existing transmission lines.

Kenya and Tanzania

Kenya currently produces about half its electricity from hydropower, with fuel oils making up about 35 percent. Kenya has also been tapping into geothermal electricity production, for which the country has great potential. Geothermal power generation currently accounts for about 200 megawatts, or 13 percent of the total installed capacity. It is seen as a more sustainable production method, one that is not affected by seasonally changing water levels, does not require the same level of upfront investments as major hydropower projects and in general is locally sourced. That last factor is important because it means that production can occur in proximity to consuming industries or population centers, limiting the load on transmission networks.

Kenya is also investing heavily in solar power plants. These plants also require a smaller initial investment in infrastructure when compared with hydropower, and they are also considered to be more reliable throughout the year. Kenya, however, is not limiting its scope to renewables. In an attempt to benefit from the changing East African energy market, Nairobi recently announced it is seeking to construct coal- and natural gas-fired power plants.

While a proposed natural gas-fired power plant in the port city of Mombasa would initially be fueled by natural gas imports from Qatar, a move toward power generation from natural gas probably takes into account the expected growth in natural gas production in neighboring Tanzania as well as some potential natural gas discoveries off the coast of Kenya itself. Tanzania could supply Kenya if a pipeline extension currently under construction from Tanzania's natural gas fields to Dar es Salaam were added to the region's pipeline infrastructure. The Kenyan coal-fired power plant makes sense as a response to recent developments concerning the expansion of coal mining in the country.

As mentioned, in the near future Tanzania will undertake a major effort to redevelop its natural gas resources, a substantial part of which could be used to boost power generation in the country. Natural gas-fired power plants already represent about one-third of Tanzania's installed electricity production capacity, but Tanzania's prospects as a possible major producer are expected to further increase the potential for natural gas-fueled power generation. While this is likely to make Tanzania fairly self-sufficient in generating electricity, the country will likely continue to support regional integration of transmission networks, a development that could enable Tanzania to monetize surplus production capacity outside of peak times.

Once production begins in Tanzania's sizable offshore natural gas fields, the country will find itself with an amount of natural gas far exceeding domestic demand. For now, Tanzania is building its capacity to use natural gas as feedstock for new power plants, and it wants to expand its electricity grid throughout the country and into cross-border regional markets. In the coming years, though, much of Tanzania's natural gas will be transformed into liquefied natural gas and exported to global markets, for instance those in South and East Asia.

Building Further Connections

Outside of the Lake Victoria region, Ethiopia, Sudan and Djibouti also engage in electricity trading. Transmission infrastructure is still lacking and needs to be completed before these countries can integrate into the same grid as Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Ethiopia exports electricity to Sudan and Djibouti on Sundays and during nights. Sunday is not a working day in Ethiopia, but it is in Sudan and Djibouti, so the surplus capacity is used to power industrial activity in those countries. At night, Ethiopia's power demand drops due to its temperate highland climate, while searing heat in Sudan and Djibouti draws more power.

Ethiopia is seeking to expand its exports. Not only does it want to increase the volume of exports to Sudan and Djibouti, but it also aims to export to other countries, including those around Lake Victoria as well as South Sudan -- which is currently not connected to other regional grids -- and Yemen, by means of a submarine cable running from Djibouti. Eventually, Ethiopia seeks to boost its current 223 megawatts of annual exports to at least 5 gigawatts per year, an increase it hopes to enact over the next 25 years. Ethiopia has already secured $1.5 billion in financing from the World Bank to construct a 1,000-kilometer (620 miles), 2-gigawatt grid link to Kenya. Nairobi has already signed a memorandum of understanding with Ethiopia, agreeing to purchase 400 megawatts per year. Yemen has signed a similar memorandum for the purchase of 100 megawatts per year once the submarine cable is in place.

To support its ambitions for power exports while meeting its growing internal demand, Ethiopia is attempting to increase its power generation capacity by transforming itself into a hub for renewable energy. Geographically, this is well within Ethiopia's capabilities. The country's potential production from hydropower, wind farming, solar and geothermal power plants could add some 60 gigawatts. The need for financing, however, is holding up the construction of the required infrastructure. To bridge this gap, Ethiopia is focusing on securing private investment -- rather than proffering state support -- by offering attractive conditions to capable companies. Several projects are already underway, including a 1-gigawatt geothermal power plant financed by a U.S.-Icelandic company as part of a $4 billion deal. A 120-megawatt wind farm is also being built on the back of a $290 million French investment. Project time overruns in Ethiopia, however, may discourage potential investors. The time to completion of such projects is on average 230 percent of that initially scheduled.

Despite the challenges, Ethiopia counts on increasing its power generation capacity from the current 2,300 megawatts to almost 11 gigawatts over the next three years. This considerable increase in capacity is based mostly on two mega-projects. The $1.5 billion Gilgel Gibe III Dam, scheduled for completion in 2015, has a potential installed capacity of 1.87 gigawatts, which would make it the highest-capacity hydropower installation in Africa. The project was about 75 percent complete by the end of 2013. A larger boost in electricity generation capacity, however, should come from the $4.8 billion Grand Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile. While this project, currently about 30 percent complete, is scheduled to start producing some 700 megawatts by the end of 2014, its total installed capacity when it is scheduled to become fully operational in 2017 would be 6 gigawatts. Recent reports about a lack of funding may imply significant delays, while the construction of the dam itself has already proved highly controversial: Egypt opposes the dam out of worries that it will disrupt the flow of the Nile River.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)