Navigating the Dragon: The China Factor and India-US Technology Cooperation

Nachiketa Thaker

20 February 2024

IRGA Jan-Feb Issue 2024

Image Credits: Times of India

Introduction:

The rapid advancement of technology has significantly shaped the geopolitical landscape, leading to new global partnerships and rivalries. One of the leading partnerships is that of India and the US in the technology sector. President Biden and Prime Minister Modi affirmed that technology will play a defining role in deepening their partnership, during the latter’s recent visit to the US in June 2023.

Interestingly, this partnership is not limited to a bilateral dialogue between the two powers but also extends to forums and summits like the QUAD. This growing relationship has been a subject of interest and concern for various nations, especially China. As the world moves towards multipolarity, albeit with bipolar features, both the USA and China are trying to sell a technology system to the world based on their ideology. While China fosters technological cooperation based on common interests, the US promotes shared values, transparency and democratic institutions that respect data protection and privacy rights.

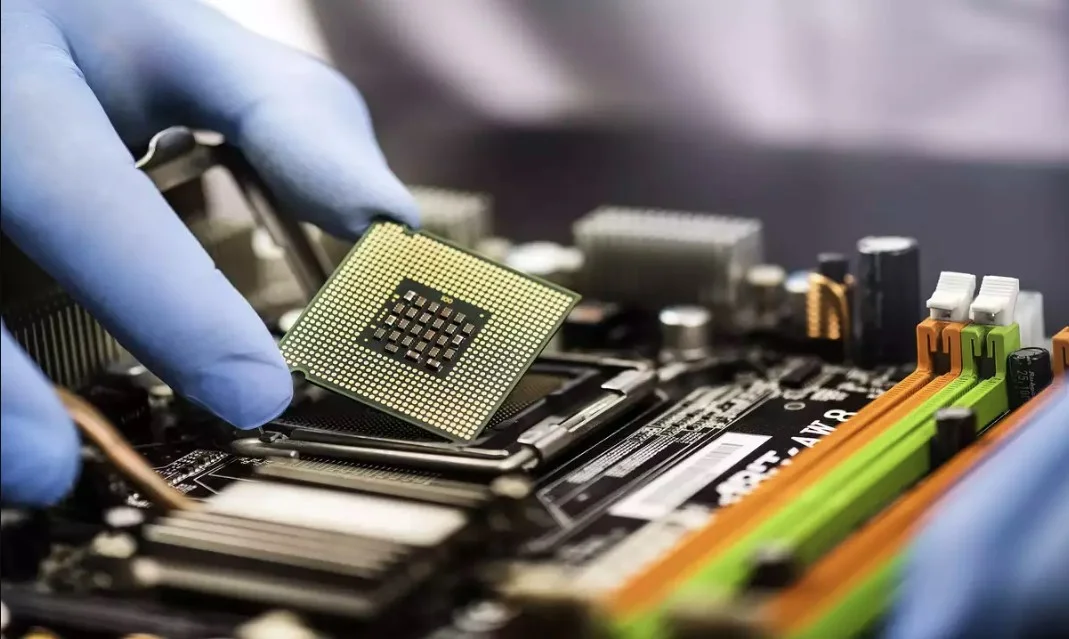

The US model is more appealing to India, as both nations seek to reinforce mutual trust and confidence through their technology collaborations. This can especially be seen in the defence sector, as India has now signed all four foundational agreements with the US (GSOMIA, LEMOA, COMCASA and BECA)[1]. Such cooperation mobilises expertise from both nations and is crucial to their strategic interests. However, India is also focusing on developing indigenous capabilities in the technology sector- like manufacturing semiconductor chips as part of its ‘Make in India’ programme. For the US, India is a potential partner, especially in the defence and technology sectors. This is primarily because the US fears Chinese supremacy in these sectors, and collaboration with India can pose grave challenges to the dragon’s victory in the technology war.

However, Indian laws seek to impose certain restrictions on American technology firms. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act passed in August this year mandates companies to get their users’ consent before collecting their personal data and gives the government authority over which data could be transferred outside the country. Although international actors like the EU through its General Data Protection Regulation also seek to impose restrictions on American technology firms (European Commission), rights groups like Access Now and The Editors Guild argue that the Indian law widens censorship and authority of the government over citizens’ data in an intransparent manner.

Nonetheless, at a time when the Indian government wants to expand the modernisation of the manufacturing and technology sectors, the US serves as a crucial international partner, and collaboration with America is seen strategically in fostering innovation and economic growth.

Hence, both countries seek to enhance their economic competitiveness in the tech sector, and their collaboration would also drive global growth besides protecting their shared national interests vis-a-vis China. Hence, it is important as well as interesting to analyse the dragon’s perspective on this growing strategic partnership.

China's Observations on India-US Technology Collaboration:

On the face of it, China seems to be unconcerned about this partnership by maintaining that the relationship between the two powers faces major hurdles. It also appears to be confident about its technological prowess and portrays that geopolitical calculations made by Washington to woo New Delhi are bound to fail.

Two major reasons are given by Chinese academics to support this argument (Xiaozhuo, 2023). Firstly, it is unclear if India would oblige to American restrictions that come with the transfer of technology to its allies. Given the fact that India is not an ally, this seems even more complicated. Secondly, China perceives that India is keen on maintaining its strategic autonomy and wants to maximise its gains from the US-China rivalry. As India has been acting like a swing state, it is unlikely that it would serve the USA’s purpose of containing the dragon.

However, hidden beneath this propaganda are China’s genuine concerns over this strategic collaboration. Firstly, the dragon takes India more seriously only when the US starts engaging with New Delhi. The Chinese economy is roughly six times the Indian economy and its military spending is three and a half times higher (SIPRI, Liang, 2023). Beijing has kept New Delhi in a diplomatic limbo over the disputed border issue and ignored India’s position on a range of issues from CPEC to Pakistan-sponsored terrorism. Moreover, India rarely finds any mention in official Chinese media like Xinhua and CGTN unless it engages with America in any manner. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning’s statement over PM Modi’s US visit that "It has been China's longstanding position that military cooperation between states should not undermine regional peace and stability, target any third party, or even harm the interests of any third party," reinforces the above arguments (Varma,2023).

Beijing’s insecurities are also driven by India’s rise. Though the economic gap between the two Asian giants is wide enough, Beijing knows that only New Delhi has the potential and ability to challenge the former in Asia. According to The Washington Post writer Max Boot, India's potential to check China's power has never been greater (Boot, 2023). Although still a lower-middle-income country, India’s demographic dividend that comes with the status of being the world’s largest population coupled with one of the world’s highest economic growth rates (second highest among G20 economies in 2022 and almost twice the average for emerging market economies) offers multiple advantages. Furthermore, a younger population in India may indicate greater openness to new technologies than China (Harvard Business Review, Dychtwald, 2021) and friendly diplomatic relations with technologically advanced democracies like the US and Israel give New Delhi a unique advantage over other regional powers.

China would be concerned that its ventures like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) and Global Security Initiative (GSI) will come under threat if Indo-US technology cooperation results in the maximisation of their strategic and military capabilities. Moreover, alliances like the QUAD have prioritised strengthening partnerships in critical and emerging technologies to maintain a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific. The plan includes the creation of a Critical and Emerging Technology Working Group and the Semiconductor Supply Chain Initiative to promote innovation and supply-chain resilience consistent with the values upheld by the member nations: namely Australia, India, Japan and the US (Xiaoqiang, 2023). This could again be considered a threat to China’s geopolitical vision for the Asia-Pacific besides concerns that the grouping’s actions are aimed against China. This is why Beijing calls the QUAD an “Asian NATO”.

China sees the QUAD as a concerted effort to contain its regional and global ambitions, thereby affecting its diplomatic strategies and relationships with other nations, particularly the ASEAN states that lie at the heart of the Indo-Pacific as well as the South China Sea disputes (Xiaoqiang, 2023). Hence, Beijing’s perspective reflects its insecurity that Washington would optimally utilise the QUAD and other alignments like AUKUS in the region to counter China in the technology and military spheres.

Economic Impact:

The deepening Indo-US technology cooperation could potentially affect China's technological competitiveness, market access, and trade relations. Competitiveness concerns the US while market access is more relevant for India. Trade relations are significant vis-a-vis both powers.

The U.S.-India initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology elevates the strategic partnership enjoyed by the two nations. It is a collaboration between the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Department of Science and Technology of India. It aims to develop and deploy advanced technologies in the Indo-Pacific region and poses a significant challenge to China (Pant,2023). Furthermore, the recent US-India joint statement for tech cooperation has identified several areas for potential cooperation, ranging from jet engine technology and advanced drones to artificial intelligence and semiconductors (White House, 2023). These areas are carefully identified, as technology forms the core component of national security in both countries.

After the Galwan Valley crisis in 2020, India banned over fifty Chinese apps, effectively restricting market access to Chinese tech giants (Pham, 2020). Companies like Bytedance (who owns TikTok) and Tencent have made huge investments in India expecting lucrative returns from the emerging market economy, comprising an expanding middle class (Pham, 2020). However, before they could earn substantial profits, geopolitical tensions resulted in their exit from the world’s second-largest internet market. Moreover, Chinese telecom giant Huawei was also kept out of auctions for developing 5G infrastructure in India. By maintaining that banning the apps would protect the data of Indian citizens from being misused by hostile elements, New Delhi sent a signal that it would not shy away from leveraging its market potential to deter China.

On the other hand, companies like Huawei, Hikvision and ZTE were already under the scanner in the US. Labelled as ‘national security threats’, they attracted US sanctions. The continued effect of sanctions implies that technology transfer to China is becoming increasingly difficult. This poses significant challenges to China’s ambitious agenda of taking a lead in AI, 5G and other critical and emerging technologies. Moreover, US tech firms are now looking towards India for their investments. This includes the manufacturing of semiconductor chips. For instance, the American memory chip company Micron Technology is all set to open a $2.75 billion semiconductor assembly and testing facility in Gujarat (Phartiyal, 2023).

To conclude, the emerging strategic partnership in the technology sector between the US and India has immense potential to test China and its limits. Beijing would most likely be a keen observer in this development and align its tech strategy accordingly.

China’s Technology Strategy

US sanctions can hurt the key tech industries in China: electronic companies, IT firms and telecoms. However, this development increased investment in innovation by 52.9 per cent in these sectors. In the decade from 2010-2020, the number of patents issued by Chinese tech firms increased by 57.6%. This also led to a significant rise in the cost of innovation, something that Chinese firms were previously able to elude through technology transfer (Chen, 2023).

However, in capital-intensive industries, the effect of regulatory policies was overcome by simply raising domestic capital investment. This includes new material industries like green materials, nanotechnology, 3D printing, material informatics and additive manufacturing. The cost of innovation was rather cut for these industries. According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), China has an edge over the US in 37 out of 44 critical technologies, which includes AI, biotechnology, energy and defence. In addition, it has been found that some Chinese firms are bypassing sanctions through third parties and cloud services (Clark, 2023).

Chinese leadership seems to have understood this phenomenon and is willing to undertake short-term loss for long-term benefits. As China’s labour market undergoes rapid changes, innovation and the indigenisation of technologies will only help China in the long run. This is something that India also aims to do, but its eastern neighbour is much more capable at this stage. Xi Jinping’s economic vision also seeks to propel China towards manufacturing high-tech products and seems less concerned about the Internet economy.

From a geopolitical dimension, Beijing may forge new alliances, strengthen existing arrangements and expand its technological influence to counterbalance the deepening Indo-US tech partnership. However, this can be particularly difficult for China at a time when strong allies like Russia and Pakistan are weakened. In addition, ASEAN states may resist China’s influence considering the South China Sea dispute. Moreover, it cannot be completely denied that Western sanctions and increasing competition from emerging economies like India would pose significant challenges to China’s objectives.

Way Forward and Conclusion:

From a strategic perspective, China will most likely view the deepening Indo-US technology cooperation as an attempt to counter its influence and potentially constrain its rise as a global technological power, as China’s economic ambitions are intertwined with its technological progress. The deepening Indio-US technology partnership may create new economic opportunities for themselves, but increased competition for China. As a result, Beijing would seek to adapt its economic diplomacy to deal with the shifting geopolitical landscape in the region.

Moreover, such collaboration may worsen the US-China and India-China rivalry. Besides, the enhancement in India’s technological and economic capabilities might kickstart a balance of power game between New Delhi and Beijing in Asia. On the other hand, China has launched its strategy for technology development. Under Xi Jinping, the country with a shrinking young population is focusing on innovation and emerging technologies, besides using third-party channels to bypass Western sanctions on technology transfer. China can also align its technology strategy with its interests-based international partnerships. However, this seems difficult for an inward-looking country with tight information control.

To conclude, it is important to understand the Chinese perspective on the deepening Indo-US technology cooperation to predict at ways in which Cold War like technology conflict could be seen in the future. It can also help to devise solutions for the same. In a world already rife with increasing regional conflicts, it is crucial to develop understanding and dialogue between great powers in order to curb the potentially destructive impact of emerging technologies.

References

- Bishoyi, S. (2022, April 11). India-US forging tech alliances since long. Now use 2+2 dialogue to push it further. ThePrint. https://theprint.in/opinion/india-us-forging-tech-alliance-since-long-now-use-22-dialogue-to-push-it-further/910983/

- Boot, M. (2023, May 18). India just passed China in population. That’s good news for America. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/05/15/india-population-china-geopolitics/

- Chen, S., & Chen, S. (2023, March 14). US sanctions boost China’s R&D investment and output in some hi-tech fields: Chinese study. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3212648/us-sanctions-boost-chinas-rd-investment-and-output-some-hi-tech-fields-chinese study?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article&campaign=3212648

- Chinese firms are finding ways to beat US tech sanctions. (2023, March 20). Light Reading. https://www.lightreading.com/regulatorypolitics/chinese-firms-are-finding-ways-to-beat-us-tech-sanctions/d/d-id/783915

- Dychtwald, Z. (2021, December 13). China’s new innovation advantage. Harvard Business https://hbr.org/2021/05/chinas-new-innovation-advantage

- Joint Statement from the United States and India. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/06/22/joint-statement-from-the-united-states-and-india

- Mukherji, B. (2023, July 3). How US deals with ‘natural partner’ India could boost defence, tech cooperation amid China tensions. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3226171/how-us-deals-natural-partner-india-could-boost-defence-tech-cooperation-amid-china-tensions

- Pant, H. V. (2023, February 17). India-US relationship in a new Tech-Order. ORF. https://www.orfonline.org/research/india-us-relationship-in-a-new-tech-order/

- Pham, S. (2020, December 11). Chinese tech companies bet big on India. Now they’re being shut out. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/12/10/tech/india-china-tech-tensions-intl-hnk/index.html

- Phartiyal,S. (2023, July 28). India sets steady path toward local semiconductor industry. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/electronics/india-sets-steady-path-toward-local-semiconductor-industry/articleshow/102203398.cms?from=mdr

- (2023, February 1). India, US are ready to break down barriers to closer technology and defence cooperation: Experts. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-us-are-ready-to-break-down-barriers-to-closer-technology-and-defence-cooperation-experts/articleshow/97512247.cms

- Taneja, H. (2023, April 17). The U.S.–India Relationship Is Key to the Future of Tech. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/04/the-u-s-india-relationship-is-key-to-the-future-of-tech

- Varma, K (2023, June 26) Cooperation between countries should not undermine regional peace, target third party: China on Indo-US defence deals. (n.d.). http://www.ptinews.com/. https://www.ptinews.com/news/international/cooperation-between-countries-should-not-undermine-regional-peace-target-third-party-china-on-indo-us-defence-deals/596570.html

- World military expenditure reaches new record high as European spending surges. (2023, April 24). SIPRI.

- https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2023/world-military-expenditure-reaches-new-record-high-european-spending-surges

- Xiaozhuo, L. (2023, June 23). Ambitious US-India plans face hurdles. Chinadaily.com.cn. https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202306/23/WS64958fbfa310bf8a75d6b4e5.html

- Xiaoqiang, F. (2023, June 16). Quad cannot prevent China’s rise. Opinion - Chinadaily.com.cn. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202306/16/WS648b9859a31033ad3f7bc87b.html

.png)

.jpg)