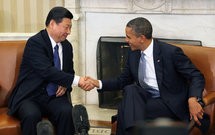

Having completed visits to Trinidad and Tobago and to Costa Rica, Chinese President Xi Jinping will head to Mexico for his second meeting with President Enrique Pena Nieto. Xi will then travel to the Sunnylands estate in California on June 7-8 for his first meeting, as China's top leader, with U.S. President Barack Obama.

Having completed visits to Trinidad and Tobago and to Costa Rica, Chinese President Xi Jinping will head to Mexico for his second meeting with President Enrique Pena Nieto. Xi will then travel to the Sunnylands estate in California on June 7-8 for his first meeting, as China's top leader, with U.S. President Barack Obama.

As new leaders of countries linked by a vast trade imbalance, Xi and Pena Nieto will likely sketch out a vision of how to boost Mexican oil exports and Chinese investment. The two countries are related primarily by commerce, and with Pena Nieto seeking to open up Mexico's energy sector and to restructure state oil champion Pemex, the incentives line up nicely for improved bilateral cooperation. China's relationship with the United States is more complicated and more strategic, and it is becoming far more difficult to manage.

The visit of China's new leader, toward the outset of Obama's second term, seems an opportune moment for the world's two biggest economies to recalibrate their relations. Although Xi and Obama's personal friendliness has been widely discussed as offering a way to overcome their nations' lack of mutual trust, the two leaders have selfish reasons for offering warmer ties. Xi has set himself up as a reformist president. The success of his economic agenda, which he will roll out later this year, will define his first term in office. He has already signaled that correcting imbalances in the Chinese economy is a priority, warning the world that the recent trend of slower growth rates will continue. Xi would like to carry out his reforms with minimal interference from the United States and its allies.

In many rounds of negotiations, Washington has demanded precisely the sort of reforms that Xi claims he will undertake. The United States knows that, for Beijing, reform does not mean remaking China's economic structure in the American image. Still, it wants the global recovery to continue and especially wants to ensure that American opportunities in China continue to grow even if China's rate of expansion falls. Washington has preferred not to confront China over the countries' ever-widening range of strategic disagreements. Instead, it has sought to profit from the existing status quo.

For decades, trade and investment have provided the means by which these two powers sideline their other disagreements, and they appear capable of keeping up this game. Ahead of the visit, there was talk on both sides of the Pacific about the possibility of China joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a regional free trade agreement that the United States has promoted across the Pacific region, ostensibly to the exclusion of China -- though the United States has always made it clear that China could join if it embraced structural reform. The idea is significant, and not unrealistic. In order to join, Beijing would need the approval not only of the United States and Mexico, but of all the other prospective members, many of whom would suspect its willingness to conform to the agreement's ambitious goals. Nor is it clear whether China would be allowed to join immediately or only after the group is formed. Still, the possibility that Beijing could join points to the willingness of the United States and China to work together, though it also indicates Beijing's awareness that it cannot afford to allow its colossal trading power to drive its Pacific partners in Asia and the Americas into an exclusive club led by the United States.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is only one example of the type of regional and multilateral framework that the United States hopes China will adopt so that its rise will not culminate in a revisionist challenge to the U.S.-dominated system. Still, the United States and China can only postpone their disagreements for so long before they seek to join incentives with disincentives. The recent revelations that Chinese cyber espionage has to some extent -- however small -- penetrated several of the United States' most advanced military systems points in the direction of American retaliation, and beyond that a cycle of cyber-strikes and counterstrikes. The possibility of escalating use of punitive measures exists in trade and territorial disputes as well.

The process of so-called containment that Beijing fears is not merely an elaborate diplomatic game that the United States can reverse at will in order to improve relations. Rather, it is the cumulative effect of all of China's competitors -- including the United States but also Japan, Southeast Asia and India -- taking what they see as necessary precautions. Just as the United States cannot dispel containment even if it wants to, China cannot forgo the chance to build effective deterrents against potential U.S. aggression.

By drumming up international support for its economic reforms and signaling a warming of relations where possible, Beijing is using tactical smarts to seek a reprieve from foreign pressure. It is doing so at a time when its internal reorganization could become hard to handle. The United States has been demanding reform, so it may give China some space to operate. But far from a harmonic melding of Xi's "Chinese dream" with the American dream, all that has happened is that both sides have agreed, as they frequently do, to sit down and talk. After that, their pursuit of national interests will resume.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)