On Jan. 19, 1915, the German Admiralty received permission to carry out a bombing raid over England's eastern coast. Two L-series airships succeeded in dropping ordnance on the towns of Great Yarmouth, King's Lynn and Sheringham, killing four and wounding 16. Although casualties were scant compared to the fighting on the Continent, the validity of long-range strategic bombing had been proven, paving the way for the development of bomber aircraft that would eventually eclipse the Zeppelin dirigible on a massive scale.

On Jan. 19, 1915, the German Admiralty received permission to carry out a bombing raid over England's eastern coast. Two L-series airships succeeded in dropping ordnance on the towns of Great Yarmouth, King's Lynn and Sheringham, killing four and wounding 16. Although casualties were scant compared to the fighting on the Continent, the validity of long-range strategic bombing had been proven, paving the way for the development of bomber aircraft that would eventually eclipse the Zeppelin dirigible on a massive scale.

The Germans used airships throughout World War I despite the high cost, significant attrition rate and comparatively low combat effectiveness. Despite being ultimately impractical as a weapon, lighter-than-air systems, commonly known as aerostats, have remained useful as a military tool in contemporary environments, particularly as a persistent surveillance platform — the purpose for which the first manned balloons were originally intended.

The first manned balloon flight occurred over Paris on Nov. 21, 1783. Roughly a decade later, the French Committee of Public Safety established an Aerostatic Corps, eager to exploit the utility of balloons in war, primarily for surveillance, mapping and aerial reconnaissance purposes, though the delivery of troops by air was considered. During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, observers in balloons were used to direct artillery fire, and it was not long before thought was given to direct aerial bombardment. In 1849, the Austrians attempted to bomb a besieged Venice from the air using unmanned balloons — they might even have succeeded, had the ordnance not drifted off course.

Balloons played their part in the American Civil War, predominantly to gather intelligence but also to provide information for detailed maps. Five years later, during the Franco-Prussian War, balloons were used to good effect by the French, overflying the blockades around a beleaguered Paris to deliver messages and supplies or to facilitate escape. The Prussians retaliated by shooting the balloons down, forcing the French to launch at night. The British use of balloons during the Second Boer War in South Africa from 1899 to 1902 was limited mainly to observation, though the Boers greatly feared the aerial platforms being used as bombing platforms. On July 29, 1899, an International Peace Conference at The Hague prohibited the launching of projectiles and explosives from balloons for a period of five years.

The Dawn of the Zeppelin

Despite the grand ideas emboldening mankind's early forays into the skies, antediluvian balloon flight was hampered by a number of extremely limiting factors. Balloons were filled with hot air or gas, prone to seepage or ignition. A bigger balloon could carry a larger payload, but it also required more volume — therefore, increased reserves — to keep it afloat. But these concerns were secondary to the real problem with balloons: They were either tethered to the ground in a fixed position, which made them an obvious target for small arms and larger guns, or they went where the wind blew, not where the crew wanted, which made them a liability on the battlefield.

Where balloons did prove their worth, however, was in opening up a third dimension in warfare. Having an elevated vantage point significantly extended the range of observation. In addition to accurately pinpointing enemy positions, an eye in the sky broadly prevented massed enemies from concealing their positions and dispositions, as they might from a ground observer. This not only aided intelligence gathering and battlefield management, but also vastly added to the science of artillery by enabling forward controllers to accurately direct their fire.

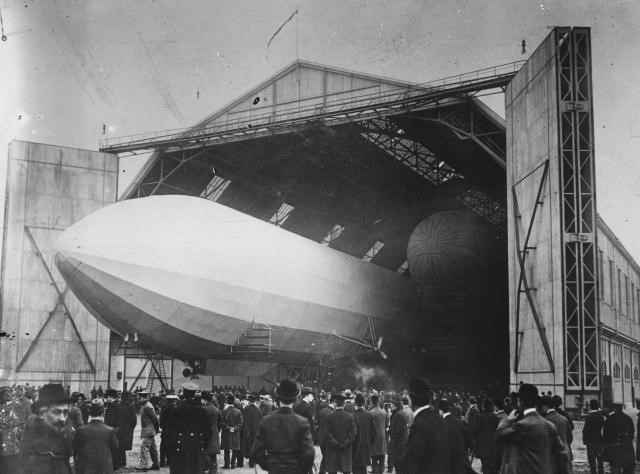

Expanding the concept, controlled free flight was achieved for the first time in 1884. A French army dirigible — an elongated aerostat powered and propelled by an electric motor — proved that directed flight was possible. The design paved the way for Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin to revolutionize the aerostat concept in 1900 with the prototype for a modular, fabric-covered, rigid aluminum dirigible containing gas-filled cells. The underslung gondola contained the bridge, cargo (or payload) space, engines, propulsion and control surfaces.

It took more than a decade for von Zeppelin to get his enterprise off the ground, by which time the Wright brothers had successfully proven manned heavier-than-air flight. Although fledgling winged aircraft were faster, more maneuverable, cheaper and easier to produce than airships, von Zeppelin's creations did have some advantages. They were designed to stay in the air for long durations and could operate at extended ranges. They could also carry extremely heavy payloads, a fact not lost on military planners eager to exploit the latest developments in industrial technology.

The first use of offensive airpower — and the official opening of a new frontier of conflict — occurred during the Turco-Italian War in 1911-1912. Italy employed both airplanes and airships for reconnaissance, eventually expanding into bombing missions. Despite the shock factor of aerial bombardment, the inadequacy of free-fall munitions and the lack of an effective aiming system were problems that would plague aircraft for years to come.

The Evolution of Air Power

The outbreak of war in 1914 provided the perfect opportunity for Germany to test the potency of its Zeppelin fleet, employing airships as tactical bombers. The attrition rate was high; within months the German army had lost half of its dirigibles, emphasizing the battlefield principle that large, slow targets tend to get heavily engaged — a factor not lost on the first tank crews in 1916. Having been literally and figuratively burned, the German army opted to keep its remaining airships away from the front, reserving them for less heavily defended targets. Though strategic bombing was still in its infancy, the Germans were quick to exploit the extended range and payload of their dirigibles, carrying out early bombing runs over Antwerp and Liege in August 1914. The ground effects, however, were often negligible because of poor aerial navigation, inferior airborne munitions and inadequate precision.

Unlike the army, which quickly lost faith in vulnerable airships, the Imperial German Navy was excited by the thought of a high-altitude surveillance platform that could dominate the ocean — particularly one that was much cheaper than an auxiliary ship and much quicker to manufacture. Exploring further opportunities to strike at the Allies, the German admiralty was quick to realize the opportunity to strike at an enemy's heartland at distance. In an effort to reduce the Allies' industrial capacity, damage infrastructure and erode morale, Germany began a campaign of aerial bombardment against select targets, most notably the British homeland.

The Race to Dominate the Skies

Over the course of the war, airships went through a number of evolutions, each designed to improve some of the inherent weaknesses of dirigibles. Unfortunately for von Zeppelin, the countermeasures against airships, of which the light combat airplane was at the forefront, went through a similar evolutionary process. The range and payload advantages of airships were effectively counteracted by their large size and sluggish maneuvering, which made them vulnerable to fighters and the weather. Defensive machine guns were effective against targets on the same level as the gondola or below, but diving attacks from above were deadly, especially when incendiary and explosive ammunition was developed for fighter aircraft. The buoyant hydrogen that kept most dirigibles afloat turned them into massive fireballs when the lifting cells were ruptured and incendiary rounds ignited the escaping gas.

Later-generation airships were significantly more powerful and could fly at altitudes in excess of 6,000 meters (20,000 feet), higher than many fighters could fly at the time. On a number of occasions this allowed German airships to achieve operational surprise, dropping ordnance on strategic targets with little to no warning. Airships were still vulnerable when ascending or descending, but the advent of fighter escorts offered a degree of protection, albeit at short range. Parasite aircraft that could deploy from an airship's gondola to protect against roving air patrols were trialed toward the end of the war, but were never operationally deployed.

The Zeppelin raids against Britain achieved mixed outcomes for Germany. British industrial output was not significantly reduced; if anything, Germany invested more resources building and deploying airships than it actually destroyed in return. The raids were also increasingly dangerous — better anti-aircraft artillery was developed that could engage targets at greater altitudes, and new generations of fighters flew higher and faster. One thing the air raids did achieve was a diversion of equipment and resources from the main war effort to the defense of the mainland.

But strategic bombing also had a psychological impact on the population. Chaos ensued when the bombing campaigns reached London, and though the casualties on the ground were paltry compared to those on the front lines, the uncertainty and fear caused by the unpredictable nature of the strikes took their toll on the home front. The investment and thought that went into insulating civilian populations from strategic campaigns while maintaining morale added to the British population's resilience to the Blitz during World War II.

As for the airship itself, the next generation of combat aircraft designed with bombing missions in mind marked the end of dirigibles' use as weapons of war. The deployment of German heavy bombers in 1917 proved far more effective than airships and led the way toward the future of strategic bombing. While primitive by the standards of German aircraft produced later in the century, the Gotha bomber proved that the future of strategic bombing rested solely on the fixed wing aircraft, rather than the grand airship.

Von Zeppelin's Legacy

Though the Germans had declared airships obsolete in a combat role by the onset of World War II, the United States used dirigibles to some effect in a naval reconnaissance and anti-submarine capacity. In the United Kingdom, so-called "barrage balloons" arrayed in clusters across the mainland were used with limited effectiveness as a method to interdict low-flying aircraft and V-1 flying bombs, but had no effect against high-altitude bombers.

With the speed and comfort of modern air travel eclipsing slow but opulent airship cruises, dirigibles in the post-war years were relegated to the position of curios or floating billboards. Defense industries continued to experiment with lighter-than-air concepts, from unmanned delivery systems to high-altitude, high-endurance surveillance platforms, and it is here that aerostats have survived. As a persistent surveillance device, tethered aerostats offer a number of benefits. They are much less expensive to manufacture and deploy than other assets, such as combat aircraft, surveillance aircraft and satellites — in fact, they are cheap enough to deploy at the tactical level. A smaller, low-altitude aerostat can dominate the ground from kilometers around a fixed position such as a patrol or forward operating base, giving real-time intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capability. Larger aerostats fly higher, furthering their observable range, and advancements in electro-optical technology offer pin-sharp still and video imagery across the visible and infrared light spectrums, by day or night. Aerostats were deployed along the U.S.-Mexico border in the 1980s as means of tracking the illegal movement of personnel or contraband before being exported to combat environments such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

Aerostats are still harried by the eternal problems of any big, floating object: They are at the mercies of the weather and are easy targets for fire from the ground or air. Although helium is inert, rendering it non-explosive, there is a reasonable logistical burden when it comes to supplying the necessary gas to keep an aerostat afloat for months or years at a time. However, compared to the running costs of comparative systems, these constraints are minor. The golden age of dirigibles at war was short-lived, but aerostats survive and continue to evolve. They may not be the fearsome weapons or luxurious floating palaces that von Zeppelin imagined, but lighter-than-air systems will continue to maintain their utility in the coming decades.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)