The Democratic Republic of the Congo's neighbors have positioned themselves to exploit and even control mineral resources in the country's most remote provinces, where Kinshasa has relatively little authority. Until recently, the Congolese government has been too weak to challenge foreign encroachment because of its battles against rebel groups, some of which are supported by other governments. Now Kinshasa is trying to reassert its control over the farthest reaches of its territory. Part of its strategy will be to pit its neighbors against one another in the hopes of improving its territorial integrity. So far, these efforts have come at the expense of Rwanda and Uganda but to the benefit South Africa.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo's neighbors have positioned themselves to exploit and even control mineral resources in the country's most remote provinces, where Kinshasa has relatively little authority. Until recently, the Congolese government has been too weak to challenge foreign encroachment because of its battles against rebel groups, some of which are supported by other governments. Now Kinshasa is trying to reassert its control over the farthest reaches of its territory. Part of its strategy will be to pit its neighbors against one another in the hopes of improving its territorial integrity. So far, these efforts have come at the expense of Rwanda and Uganda but to the benefit South Africa.

Angola hosted a summit with members of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region on March 25. The meeting provided an opportunity for the Congo and other central and southern African nations to identify and discuss their national security, political and economic interests. Though discussions probably entailed ancillary issues such as the conflicts in the Central African Republic and in South Sudan, the primary focus of the talks was more likely central Africa's mineral extraction and transportation industry. Those who attended were not there to reach a consensus on how to cooperate in the Congo; rather, they were there to advance and defend their individual intervention plans.

Lingering Security Concerns

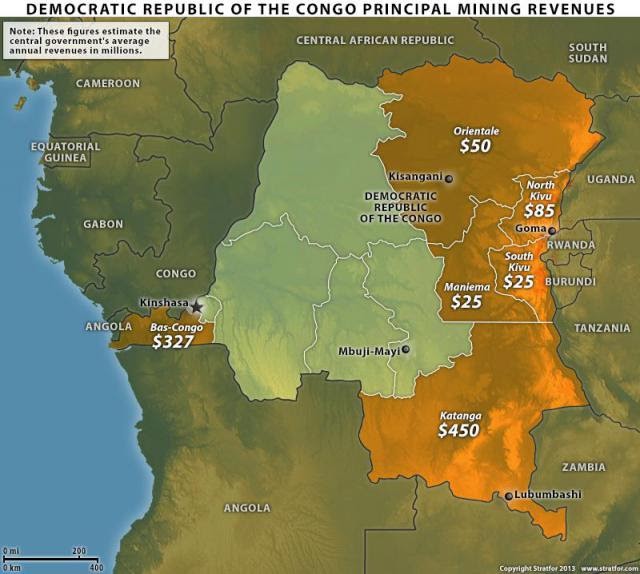

For years, the Congo's vast, insecure and mineral-rich geography has attracted the interests of its central and southern neighbors. The government is seated more than 1,000 miles from the eastern and southern provinces that contain extensive mineral deposits and potential oil and natural gas deposits. Countries such as Uganda, Rwanda, South Africa and Angola -- some of which are closer to these deposits than Kinshasa -- are trying to formally and informally exploit the Congo's resources.

For Angola, Rwanda and Uganda, the decisions to meddle in the Congo are informed by their security concerns. All three sent forces into the Congo during the country's civil war, which took place in the mid-1990s and resulted in the collapse of the Mobutu Sese Seko regime. Afterward, they wanted to ensure that whoever took power would not let Congolese territory be used as a staging ground for operations against their respective governments, as it was under Mobutu.

Though nearly 20 years have passed since the civil war ended, the specter of rebel insurgencies has lingered, prompting the governments of Angola, Rwanda and Uganda to adopt an aggressive policy of stamping out rebellions before they constitute a coherent threat, hence their propensity to intervene in the Congo. Congolese President Joseph Kabila does not support rebel forces, but neither does he have the ability to secure the extreme reaches of his country.

The combination of the Congo's mineral wealth and the precedent of operating in the far stretches of the country have given Kampala and Kigali a highly lucrative opportunity to justify and sustain their presence in the country. Sometimes this manifests not as support for rebellions but as legitimate infrastructural development. Angola, South Africa, Uganda and Rwanda are developing road and rail infrastructure that enable them to move mineral resources and materiel in and out of the Congo.

Angola is finishing the construction of its Benguela rail line, which means to connect Congo's Katanga province with the Atlantic Ocean. Rwanda and Uganda are cooperating with Kenya to construct a road, rail and pipeline network that will integrate them with Congo's Orientale and North Kivu provinces (plans for an extension to South Sudan are underway, too). South Africa, which sees Congo's Katanga province as an extension of the southern African mineral belt that Pretoria has long sought to dominate, has promoted the North-South Corridor, a reliable supply chain route that connects to the Indian Ocean.

Diversifying Foreign Backers

That all these projects compete with one another benefits the Congo as it tries to reclaim some of its sovereignty. To that end, Kinshasa has made some gains against Rwanda and Uganda, thanks in part to the United Nations and South Africa.

By itself, the Congolese government cannot prevent its neighbors from encroaching on its frontiers. It repelled Rwandan and Ugandan incursions only with the help of the U.N. Intervention Brigade, to which South Africa contributed a substantial number of soldiers. U.N. peacekeepers dislodged and largely expelled M23 rebels used by Rwanda to justify its presence in North Kivu province. Peacekeepers have since tried to repel other militant groups in eastern Congo, including a Hutu militia and Ugandan rebels of the Lord's Resistance Army and the Allied Democratic Forces.

Notably, the defeat of the M23 militia has aggravated a political conflict between Rwanda and South Africa. Though it has not admitted to it publicly, Kigali likely blames Pretoria for its participation and probable leadership in the U.N. Intervention Brigade that ultimately defeated the M23 rebels.

Pretoria's participation is hardly surprising. South Africa has long been interested in the Congo's southern provinces, where diamonds, copper and cobalt abound, but it is growing more interested in gold and potential oil and natural gas deposits in eastern Congo. This aligns with the Congo's current strategy of avoiding entanglements with Rwanda and Uganda.

Because of limited infrastructure linkages, southern Congo has been effectively disconnected from eastern Orientale and North Kivu provinces; the North-South corridor has become the only dependable route for South Africa to transport commodities to and from the Congo.

In theory, this route could enable Kinshasa to circumvent Rwanda and Uganda. But as much as the Kabila administration benefits from South Africa's political, military and economic support, it does not want to simply replace one dependency for another. Kabila -- or at least his allies -- are floating ideas that would possibly amend the constitution or otherwise permit Kabila more years in office, should national elections be held in 2016; being able to show that he represents the entire country's interests, and not just those close to the capital, would help him in this regard. Using South Africa to dislodge Rwanda's and Uganda's grip on eastern Congo may be what Kinshasa required in the short term, but turning to Pretoria for all of its security and supply chain requirements would not be a long-term option for Kinshasa.

Ultimately, none of these options alone changes the Congo's geopolitical dilemma. Because of their proximity, Uganda and Rwanda will probably remain a supply chain upon which the Congo will have to rely. And lingering security concerns mean that Kampala and Kigali will maintain their presence in eastern Congo, with forces ready to intervene again if anti-regime rebels reconstitute into a coherent threat.

For its part, Pretoria will gain additional economic concessions for supporting the Kabila administration, but the Congo will not create a new dependency as it weans itself off Kampala and Kigali. The country may consider constructing its own road, rail and pipeline infrastructure to avoid foreign supply chains altogether. But its geography will make this option challenging and expensive, though not impossible. In any case, financial constraints dictate that Kinshasa continue to diversify its foreign backers to reclaim sovereignty.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)