The second half of 2014 saw the mainstream media focused on the West African Ebola outbreak and the potential for a widespread epidemic. But the turn of the calendar year has arrived with much more optimistic news for world health. An article published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature reported the discovery of a new antibiotic. Representing what could very well be a paradigm shift, the paper chronicles two very important developments. The first is that this new antibiotic targets the bacterial cell in a way that prevents the easy development of resistance.

The second half of 2014 saw the mainstream media focused on the West African Ebola outbreak and the potential for a widespread epidemic. But the turn of the calendar year has arrived with much more optimistic news for world health. An article published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature reported the discovery of a new antibiotic. Representing what could very well be a paradigm shift, the paper chronicles two very important developments. The first is that this new antibiotic targets the bacterial cell in a way that prevents the easy development of resistance.

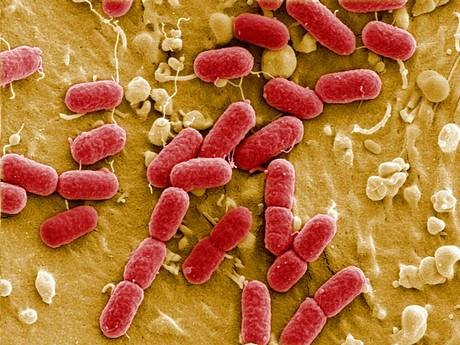

Teixobactin, the new antibiotic discussed in the article that works by targeting lipids that are essential to forming the cell wall, did not exhibit any antibacterial resistance when tested against bacteria mutated in the lab. The second development is perhaps even more groundbreaking. The researchers developed a new methodology to grow and isolate potential antibiotic targets. Up to this point, only a fraction of possible compounds could be cultivated in the lab, limiting researchers' ability to test new targets for activity against bacteria. This new method opens the door to a whole new world of possibilities.

Dangers of Drug-Resistant Bacteria

These developments are a huge breakthrough for biology and medicine, but what does this mean for us as a geopolitical forecasting firm? Ebola showed us that just because a disease is covered in the news does not mean that it has a global or immediately obvious geopolitical impact. However, the potential for economic disruption from epidemics and endemic diseases, through lower production and increased expenditures because of treatment or trade restrictions, remains a possibility that would have geopolitical implications. Malaria, for instance, hinders the economic growth of developing countries looking to take advantage of low-end manufacturing opportunities as China's economy shifts. And while this new drug will not have an impact on the malaria epidemic, it could stop another in its tracks.

Drug-resistant bacterial infections are a growing problem, one that until Wednesday did not have a good solution. Many antibacterial agents utilize the same chemical scaffolds or backbone, some of which have been around since the 1940s. Bacteria can and do easily mutate to adapt, and the overuse of antibiotics has contributed to the development of antibacterial-resistant strains of a number of diseases. Hospitals are seeing a rising number of MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) cases, and drug-resistant tuberculosis is spreading throughout the globe. The high cost of treating drug-resistant tuberculosis, especially prevalent in Russia, Central Asia and Eastern Europe, put increased pressure on already struggling economies. The situation had reached a point to where speculation as to what a post-antibiotic society would look like was not completely unwarranted — and some of the scarier scenarios looked much like a pre-antibiotic society.

With little incentive for pharmaceutical companies to invest in expensive drug development, in part because of the development of resistance inherent in many classes of antibiotics, there had been little development or advancement in the field in decades, and resistance continued to rise. Teixobactin or another yet-to-be-discovered molecule could change that. Teixobactin attacks a specific family of bacteria — gram-positive, which includes the bacteria that causes both strep and staph infections — in a way that is not prone to the development of resistance. Resistance is less likely because of where the drug is active. Whereas some other antibiotics target proteins, teixobactin is believed to target lipids. The formation of proteins lends itself more easily to mutation than the synthesis of lipids. In initial tests, teixobactin showed efficacy in fighting drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Exciting, but Not Immediate

Teixobactin is not a panacea. It does not work on gram-negative bacteria, a family that includes the bacterium that causes cholera. That is where the second and perhaps more important finding of the paper comes into play. The biological and medical communities now have a method to access a wide array of possible drugs that previously could not be studied. To put into perspective the staggering number of new possibilities, previously, only 1 percent of microbial targets could be cultured or grown in a lab, which is required to test for antibacterial activity. This new technique, which utilizes special equipment — a device called the iChip, which enables numerous bacteria to be grown and tested in their natural environments, such as soil, instead of using traditional laboratory methods — opens the door to the other 99 percent.

However, while incredibly exciting, this discovery does not necessarily have immediate geopolitical implications. It will not necessarily make drugs cheaper or more readily accessible to developing nations. It will also take several years to develop teixobactin and many more to discover other new drugs. What it really gives is an insurance policy of sorts. Disease outbreaks are hard to predict and rarely have global geopolitical impacts, but when they do, there is the potential for those implications to be staggering. The fear remains that an outbreak on the scale of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 could occur, and in a world that has become far more globalized in the past 100 years, the effects would reverberate through the world much more quickly. Widespread infections, decreased productivity, trade restrictions and border closures could all have economic ramifications that would matter at the geopolitical level.

And while this new discovery does not protect against viruses or parasitic diseases, it does provide a new set of weapons against bacterial infections. The "zombie apocalypse" may still come, but this recent technological advancement makes it far less likely to be in the form of drug-resistant bacteria.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)