Ben Sheen: Drug resistant staph infections kill about 19,000 people per year in America alone. What's been done to reduce that number of deaths or deal with the drug resistant infection?

Ben Sheen: Drug resistant staph infections kill about 19,000 people per year in America alone. What's been done to reduce that number of deaths or deal with the drug resistant infection?

Rebecca Keller: We're starting to see a resurgence of antibiotic research recently. It's a field that had been pretty stagnant for decades. And over the course of the past year or so,

we've seen several exciting developments in terms of new methods for discovering potential targets as well as a few new candidates for antibiotics in the future.

Ben: So what do you think the wide reaching implications of this will be? So how can this actually improve treatment in the future?

Rebecca: So we have to keep ahead of the bacteria. Bacteria are going to evolve. They're going to develop resistance to the current existing treatments. So, when you think about antibiotics, they're all the same scaffold. So it's kind of like building a house, you build it on the same frame, but the outside of the house looks different. But the bacteria learned to adapt that scaffold. So you're looking for a whole new scaffold. You're looking at a skyscraper versus a house of something like that. And so looking at these new scaffolds, you want to look for ones that can't develop resistance.

So teixobactin, which was, the paper on that was published last month that targets an entirely different part of the cell. So it doesn’t have the potential to develop resistance the same way current antibiotics do. So you're looking for a whole new solution. You're thinking outside of the box. And in doing so, that allows you to sort of stay ahead of the bacteria as they evolve as well. They're just trying to survive.

Ben: So what do you think of the broader geopolitical implications of this? And how we're going to see this expand in the world?

Rebecca: So when looking at disease, we're not always going to see a geopolitical impact. There is certainly the potential. Tuberculosis costs $12 billion globally every year, and malaria certainly hinders the economic development of a continent like Africa or parts of Asia. But there's not always an implication.

Drug development is still expensive and these new techniques that have come out in the last several months, whether it be computer screening to look at a whole bunch of different candidates or growing them specially in the lab like we couldn’t before, it does open a wider array of possibilities, but it's still under the same old system where it's academic research or pharmaceutical research. It's still very expensive and still very hard to distribute, so it doesn’t have the potential to reach the multitudes that would be needed to have a really serious geopolitical impact from the drug itself.

But when we think about the spread of disease and why we're worried about the development of antibiotic resistant bacteria, its, we're looking at trade restrictions. We're looking at reduced productivity of countries. Those all could have geopolitical impacts in the future. It's just not known. So everyone goes, the big geopolitical disease that everyone comes back to is the 1918 Spanish Flu. And that was a huge epidemic that had serious implications across the globe. And that could happen again. It's not necessarily that it will happen again, but that's the fear, whether it's through a virus or whether it's through drug resistant bacteria, preventing that is the ultimate goal. And this is, these new antibiotics do go a long way to help that, but there are still hurdles to overcome in terms of distribution and in terms of development.

Ben: And it's always tricky to gain funding for a potential threat that may or may not manifest. With something like Ebola, the most recent outbreak we saw in Africa, that fact alone sparked a lot of funding and research and prompted people to actually give money to the cause. Whereas preparing for some future plague it's a difficult thing in some ways. What do you think the future applications will actually be? How are we going to see this develop?

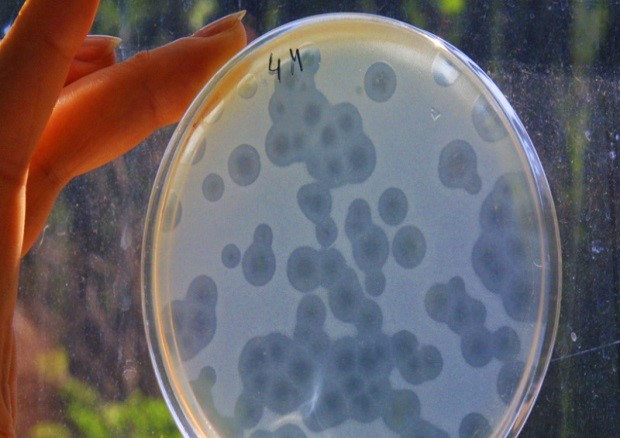

Rebecca: So that was part of the reason there was such stagnation in the antibacterial development. There was just no incentive for the pharmaceutical companies to invest money when they knew that the bacteria were just going to continually evolve and beat the new drug. The incentive is antibacterial resistance growing. It's becoming a growing problem as people misuse antibiotics. It allows for development of resistance faster. So it’s a growing problem. We're seeing more cases in hospitals of drug resistant staph infections.

Drug resistant tuberculosis is a huge problem in poorer areas like Former Soviet Union. And so it is an emerging problem. There is that incentive to now invest in ones that won't develop resistance. So there's still not the financial incentive to invest in the old model because you'd just be fighting a losing battle. But there is an incentive to come up with these new methodologies, these computer screens, these new methods of groin microbes in the lab that allows you to access more potential targets. That’s where the financial incentives is. That’s where the field is moving, in terms of finding new targets.

Ben: So clearly we're looking at some kind of time delay before this is actually operationalized.

Rebecca: Every time you hear about a new antibiotic that’s been successful in mouse testing, you're still talking years of research to get the drug through human trials and then into actual use. The Ebola vaccine was extremely accelerated. And even then we're talking, it's going to be the crisis will be over before the vaccine is actually able to be used.

Courtesy : Stratfor (www.stratfor.com)