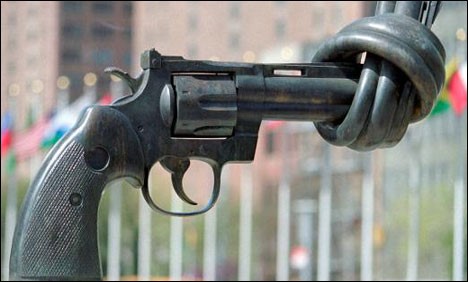

Early this April, UN voted by 154 votes to three to regulate the $70bn global trade in conventional weapons in an attempt to halt the proliferation of violent conflict and human rights abuses around the world.

Early this April, UN voted by 154 votes to three to regulate the $70bn global trade in conventional weapons in an attempt to halt the proliferation of violent conflict and human rights abuses around the world.

The new regulations will bring the gargantuan global business in small arms and light weapons, as well as tanks, armoured vehicles, military jets, helicopters, battleships and missiles under the same sort of international controls that have long applied to nuclear, chemical and biological weapons.

Human rights groups like the Amnesty International hailed the decision. Kate Allen, head of Amnesty International UK, called the treaty a milestone that would regulate "the illegal flow of arms to warlords, tyrants and despots around the world, a treaty that could save the lives of millions and help prevent conflicts like those in Mali or Sri Lanka ever happening again”

In fact there can be no quarrel if the objectives are as stated and genuine human rights violations are protested against and measures taken to check them. There have been instances where the international community has acted effectively. Equally there have been cases where allegations of human rights abuse have been used as a political tool to cow down a country.

Public memory being notoriously short, it is worth recalling the harrowing time India went through in the 80s and early 90s when year after year it was hauled up at the UNHRC meetings in Geneva over alleged human rights abuses in Punjab and J&K.

Amnesty International was in the forefront of the campaign against India; its frequent reports bordered on a regular inquisition. Amnesty’s was a formidable name then; it was the acknowledged high priest of human rights worldwide. But by some design or circumstance the focus of its reports was invariably on the developing countries and the eastern bloc.

Within the developing world there were some notable exceptions; for instance Amnesty rarely ever found fault with the state of affairs in the Gulf States. The rumour among diplomats maintained that Britain had vital commercial interests there. Pakistan too got off lightly on the odd occasion that it was criticised. This was strange especially at a time when its Army’s atrocities were widely acknowledged to be regular and widespread in many parts of Pakistan. The status of Mohajirs was particularly deplorable. One explanation for Amnesty’s benign treatment of Pakistan was the critical support it gave to USA in driving the Soviets out of Afghanistan.

India, however, was no one’s great favourite. It was therefore a convenient whipping target for Amnesty. It published with remarkable regularity reports about the alleged human rights abuses in one or the other part of India. But its principal focus was on Kashmir. It was also amazing that in a country of over one billion, Amnesty should find fault mainly with the state of affairs in the thinly populated Kashmir. Invariably, its reports damning India were timed to appear just before an important international meet; especially one concerning Human Rights.

Everything was synchronised to perfection thereafter. Following up on that report, a press campaign against India used to start off as a matter of routine. One after the other, the western press would carry sensational reports of human rights abuses alleged and detailed in that report. The contents of that report provided fodder for the debates in the UN fora damning India. Sometimes these reports also formed the basis of the resolutions that were passed against India almost routinely every year in Geneva and New York. Meanwhile in the UK and many other western capitals the local interest groups would get busy organising demonstrations in front of the Indian missions. It was a well oiled machine that seemed to spring into action every time an Amnesty International report against India was issued.

All this gave nightmares to the Indian establishment. They were routinely surprised by the allegations contained in these reports. Therefore the period before October-November every year was particularly crucial because that is when the all important Human Rights Council meets in Geneva.

Usually Amnesty International issued its India focussed reports in September; the month or so preceding the Human rights council’s meeting was enough time for a full fledged propaganda offensive.

But Amnesty and its reports were far from my mind as I walked jauntily into the Indian High Commission one sunny morning in September. The sun light filtering in through the picture glass windows of my office brightened my mood further. Enthused by the energetic spirit of that day I began busily to scan my mail; tossing an unread dossier in the in tray and flipping a casually glanced letter in the out tray. I was about to dismiss a brochure similarly when the picture on its cover caught my eye. The caption below the picture said; “A Kashmiri widow mourning the victim of human rights abuse.”

“A Kashmiri widow….,” I whispered worried. I could sense instinctively that this was trouble. But who is this brochure by, I wondered? That curiosity was soon satisfied when I looked up at the mast head. Sure enough it was an Amnesty International publication. And it proclaimed proudly that it was a special investigative issue on human rights abuses in Kashmir based on the testimony of the Kashmiri widow shown in the picture.

Suddenly, that otherwise bright day turned grim for me. The sun light was still filtering into the room through those large windows but the glory of the day was lost to me. The report was strident enough to make a convincing case for India bashing in Geneva.

Yet something about the picture bothered me. It didn’t seem right somehow. To me the lady in the picture looked far too dark to be from Kashmir. But I am not given to impulsive flashes. I wanted to double check, and be absolutely sure. I called in a few of my staff and shared my doubts with them.

They looked at the cover from every angle and examined it minutely. And they took their time about it. Eventually a large lens was summoned from the depths of the high commission’s stores. Finally they nodded in agreement with me that the woman in picture could not be from Kashmir. She seemed to belong to some other part of India.

Next, I consulted some of the Indian journalists based in London. They too concurred that the photo didn’t seem right. At this double confirmation I decided that the time had come to pursue this case further; and eventually to confront Amnesty. But before doing that I wanted to be absolutely sure of my ground, because Amnesty was an International Holy cow then. It was known to zealously guard its turf, and it moved quickly to demolish anyone who so much as dared point a finger at any of its reports.

The next part of the plan was therefore as critical as it was sensitive. One wrong move and Amnesty would become wise to our efforts to get at the truth behind that report. So at first I asked one of my colleagues to contact the photographer who had been given the credit for that cover photo.

It turned out that this man, who used ‘KASH’ as his acronym, was an Italian national. He was a freelance photographer who worked fairly regularly on a commission basis with the Amnesty International. He was also a frequent visitor to India. This piece of knowledge turned out to our advantage because his India assignments were a great source of revenue for him and he didn’t want his Indian visa to be cancelled. This is what impelled him to come out with a shocking piece of information.

Being a practical man, he knew that it was important to protect his personal interests. Amnesty International could look after its own interests. Once that was clear to him he admitted readily that the woman in the photograph wasn’t from Kashmir at all.

“Where is she from?” He was asked.

He admitted then that he had taken that photograph somewhere in Kerala. It was on a chance whim that he had chosen that setting, and he had used a local model to bow like a mourner at an old grave. He had not hidden that fact from the Amnesty International when he showed them his photo album from this latest trip to India. But for some reason this particular photo had appealed greatly to them, and regardless of its location they decided to select it for the brochure’s cover. They were confident that no one would have the time or inclination to examine it closely and spot the difference. As in the past they would remain unchallenged.

This admission by KASH should have been evidence enough, but I wanted to build a fool proof case and to have more people on my side. I was in no hurry because I wished to confront Amnesty only with the clinching proof. So the next step in our pursuit was to build a watertight case by getting his confession on tape.

Two Indian journalists volunteered to help. They interviewed him and got on tape his confession that the photo was a forgery and the fact that the accompanying report inside the brochure by Amnesty International was largely a fabrication.

This additional confirmation, and on record, was sufficient for me to challenge the Amnesty International. At first Amnesty reacted with full venom; calling us liars and challenging me personally. There were debates between their luminaries and me on almost every major TV and radio network in UK. They were so vehement in their denials that sometimes I used to wonder in private whether we were the ones who had erred. But I could also notice that as I stood my ground in media debates their confidence was beginning to slip. They were becoming increasingly more defensive.

The clinching blow against Amnesty came through a young British-African journalist who was working for The Telegraph. I explained my case to him and shared my suspicion about the method of Amnesty’s working and its motivations. Obviously, he would have cross checked the information further and must have followed it up with extensive research of his own. The article that he wrote eventually was in the finest tradition of investigative journalism. That article in one of the better known British newspapers doomed Amnesty. A number of other articles followed in the British and Indian press. Each new day brought in yet another humiliation for Amnesty, and finally in a rare act it issued a formal apology owning up to the forgery in the photograph.

That year we slept contentedly through the Human rights session. As a matter of fact Amnesty could not recover from the ignominy of that blunder for a long time thereafter.

But I was not fully satisfied. I had the nagging feeling that something was eluding me. To get to that missing link I wanted to find out the real story behind the story that we had discovered so far. Was there a deeper conspiracy to it? Why was the Amnesty International so obsessed with India? Why were its reports timed to come out just before a major human rights conference? And why did Pakistan seem to be in with the information well in advance?

The way I saw it there was no rational reason for the unhealthy zeal with which Amnesty had pursued India. What then was the nature of the hidden force compelling it towards that path? Was some outside force influencing its policies and its decisions? This question kept bothering me. Once again I had to put my touristic pursuits on hold. Instead, I put my energies back to the mysterious case of Amnesty again.

Over the course of the next few weeks a fuller picture began to emerge. It was frightening that an internationally known body such as Amnesty should have allowed itself to be manipulated in the way that it was. The modus operandi was simple. It turned out that a large number of its membership in the UK, as indeed in many other parts of Europe, consisted of people of Pakistani origin.

The membership fee then was just about 7 pounds. It was low enough to be affordable by almost everyone and for those who could not pay there was always the ever resourceful ISI ready to help. As a result the Pakistanis settled in the UK formed the single largest group of Amnesty membership in UK. This piece of evidence came as a surprise because the Pakistanis based in UK were known to aggressively promote their agenda and their interests, but they weren’t particularly vocal on global issues like human rights.

This mass enrolment by the Pakistani origin people in Amnesty International was therefore uncharacteristic behaviour by an otherwise insular community. On the other hand, and taking a generous view, I asked that if such a large number of people had opted to become members of an organisation like the Amnesty International, were they doing so out of a concern for the state of affairs in the country of their origin; in this case Pakistan.? But that was clearly not the case because this group showed no concern about the worrisome conditions back home. Nor were they interested in matters like the status of women, or that of the minorities in Pakistan. In sum they showed no interest at all in subjects which sensitive and politically aware members of a body like Amnesty should be concerned with. Instead there was just one subject that seemed to engage them; and that was the issue of human rights abuses in India.

Whenever Pakistan felt the need to raise the Kashmir issue to a new international pitch, it advised its nationals that as members of the Amnesty International they should petition the organisation to take up the issue at international fora, and to commission reports on the alleged human rights abuses taking place there. As if on cue, a flood of faxes, emails and letters would begin to arrive at the Amnesty offices urging it to act and incite the international conscience. Amnesty responded promptly to these petitions and appeals from a large body of its members. That was the trigger, but Amnesty itself was biased too. It was natural then that it should come up regularly with anti-India campaigns.

It has, however, remained a mystery to me as to why no one in the Amnesty hierarchy saw through this game; or the fact that there was something wrong about the petitions which seemed to flood Amnesty offices according to a fixed time table!

Now that the Arms treaty has given enormous powers to Human Rights groups, they would have to ensure that they are not used as a tool of political convenience. Then, both the genuine suppliers of arms and the otherwise responsible states will suffer. There is also the intriguing aspect about the rather tame manner in which state and non-state actors who sponsor terror have been let off in this treaty. Was this omission because our negotiators failed to present an effective case? Perhaps that was the case. Equally, we may have also failed to articulate effectively our concerns about the misuse of the clause concerning human rights. It is possible that these failures may come to haunt us in the years to come.

*The author, Rajiv Dogra is an Indian diplomat, and writer. He has written this piece exclusively for irgamag.com