No discourse nearer home or afar on India's geo-strategic imperatives for the 21st century has been complete without a strong and at times repeated reference to the 'String of Pearls' theory involving China. A theory floated by western strategic thinkers, it had takers in India immediately afterward - to try and ward off the threats from China. Now, it seems to have more takers in the nations of the proponents of the theory. Many are actively engaged as much in India's neighbourhood as with India, with which they have strategic cooperation agreement or arrangement. Some of these bilateral arrangements may still be in the pipeline but that does not alter the course, either in their geo-strategic appeals to India or their own geo-strategic appeal for some of India's neighbours.

No discourse nearer home or afar on India's geo-strategic imperatives for the 21st century has been complete without a strong and at times repeated reference to the 'String of Pearls' theory involving China. A theory floated by western strategic thinkers, it had takers in India immediately afterward - to try and ward off the threats from China. Now, it seems to have more takers in the nations of the proponents of the theory. Many are actively engaged as much in India's neighbourhood as with India, with which they have strategic cooperation agreement or arrangement. Some of these bilateral arrangements may still be in the pipeline but that does not alter the course, either in their geo-strategic appeals to India or their own geo-strategic appeal for some of India's neighbours.

Nothing explains the emerging Indian predicament than the recently-signed MoU for the US to gift a 'border management system' for Maldives, after the Government of President Mohammed Waheed Hassan Manik had cancelled the existing one with the Malaysian firm, Nexbiz. The Waheed Government had offered reasons similar to those that it had proffered in the case of Indian infrastructure major, GMR Group, for the cancellation - though the issues were more complex and even more politicised in the latter case for a variety of reasons. The Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) of former President Mohammed Nasheed, which had condemned the Nexbis cancellation as strong as the GMR, is yet to react to the new MoU for the US 'gift'. The Malaysian Government, which at the height of the GMR cancellation controversy, had worked hard on the ground to try and save the Nexbis contract - it was against payment - too has maintained silence. Or, so it seems.

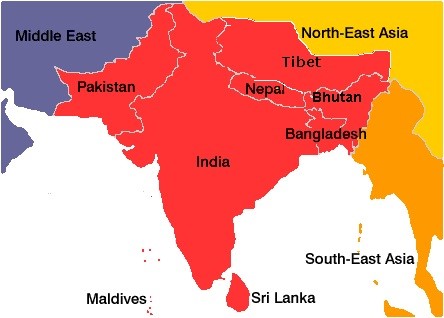

Maldives is not the only nation in the Indian sub-continent after domestic difficulties of some kind or other. The US is there already in Afghanistan and Pakistan, to a greater or lesser degree, both militarily and otherwise. The American influence would continue in these countries even after the planned and promised withdrawal of NATO troops from the region. If anything, Afghanistan could become the alternate or accompanying theatre for an emerging and at times inevitable 'cold war' of the 21st century. Already, neighbourhood nations in various combinations - the list includes China, Russia, Pakistan and Iran - have been talking to one another. India is caught in the middle. It cannot count on its US strategic partner as much on it could count on the erstwhile Soviet Union, particularly in terms of not pursuing a South Asia policy independent of Indian concerns, interests and consultations with New Delhi.

Apart from Afghanistan and Pakistan, the past years witnessed increased US involvement in countries such as Bangladesh, where the American Ambassador of the day was seen brokering peace between the conflicting political stake-holders and in brining in the armed forces to run an 'election-eve government' the last time round. It should be said to the credit of Amb Patricia Butenis that the armed forces returned to the barracks once the people of Bangladesh had voted in the Awami League back to power, one more time. In Myanmar and in Nepal, where again military junta and Maoists respectively had held sway, 'democratisation' has had the American - and not the Indian footprint. Today, in Sri Lanka, where India used to be the sole external power that the Government, the political Opposition and the minority Tamils - and the Muslims too, to an extent -- had regarded with respect, the US is all too visible through the UNHRC process.

'China factor' and more

It would not have been an easy task for a large and strong nation like India to carry the Governments and peoples of smaller neighbours with it, as they have more fear of the unknown in bilateral equations of the kind. The domestic developments in these countries - more than nearer home (Tamil Nadu in the case of Sri Lanka, for instance) - dictates that New Delhi is not seen as an 'interventionist' force of some kind. As the experience of the past has shown, stake-holders in these countries want India in their midst only on their selective terms, not even for helping them to achieve the 'common good' of their respective nation as a whole.

Given the complexities of geo-strategic and location advantages some of them (purportedly) enjoy and the increasing pulpit-threats flowing from the 'China factor', New Delhi, still licking its wounds of 1962 vintage, cannot but be cautious, not only about Beijing's intentions and reach. It also has to be cautious and concerned about the limited capacities some of India's neighbours have in exploring and exploiting the limited advantages that they still enjoy viz India. While evaluating the Indian position(s) based on what it can do in any given circumstance and the larger global mood, New Delhi still needs to take into account the geo-strategic advantages that India has to offer, strategic partners - existing ones and emerging possibilities, and explore and exploit them, as well.

The Indian perception on these matters would still be conditioned, and hence impeded by its concerns about a raising China and its intentions, influenced as both are by existing and emerging scenarios on the bilateral front, and 'multilateral front' if one were to include Pakistan as a third arm in the India-China equilibrium after the 'un-fought war' of 1962, that too, independent of India-Pakistan equations, which have been on a see-saw all through, instead. In the emerging context, with the US and its known and identifiable and trusted regional allies making inroads into what is acknowledged as India's 'strategic backyard', they have 'out-sourced' part of America's larger strategic concerns in what has for them emerged as the Indo-Pacific region (focused and narrowed down from Asia-Pacific) to India, Washington also seems to be wanting to develop independent modules of American presence in India's own neighbourhood.

Filling neighbourhood vacuum

Even after the military withdrawal from Afghanistan, the US will have its naval presence in the Indian Ocean neighbourhood of India and the rest of South Asia. On land, it seems to be filling in a diplomatic and developmental vacuum, created by China's exit or purported down-gradation, for which India has worked through the past years with and on individual nations. If someone thought that New Delhi would itself fill the vacuum, where none existed until China had arrived in the first place, that does not seem to be happening. In the short and the medium-term, India may have to choose between China and the US as the 'global power' that it could accept in the immediate neighbourhood. Over the long-term, however, New Delhi needs to ask itself if that is what it wanted, and wanted to continue, too.

For India, the 'String of Pearls' does not stop with China. The emerging pattern of an 'exiting' or less influential China getting replaced by the US - and long-term committed allies of the US - has a message of its own. For now, the shape of the Indian economy may not encourage India's neighbours to take it as seriously as they had been doing for over a decade now. They had hoped to share India's prosperity. That did not happen, whatever the individual case and independent reasons. Such being the case, the developmental assistance even in that period used to come from China - and India could not stop it, or seen as stopping it, either. That was also when the US and the rest of the western economies had hit their lowest since the days of 'Great Depression'. Today, the small change in Uncle Sam's pocket, which is what many of these nations will be satisfied with, in the interim, is going to them.

Need for national discourse

For India to be taken seriously by its neighbours, and other friends and adversaries alike, it has to be clear in its mind as to what it is and where it is headed, and where it wants to go - and can actually travel to. The post-Cold War, 'reforms era' riot of ideas put India already in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans - at least in the minds of the 'strategic community' in New Delhi. The 'String of Pearls' brought them closer home to the Indian Ocean, where alone India belongs just now, as in the centuries past. In the midst of economic re-evaluation of the self, New Delhi needs to flag a national discourse on India's strategic priorities and goals. Has it already over-stretched its geo-strategic ambitions and goals, and has spread the available and anticipated wares this in the question for which India needs to have an open and transparent discourse, leading to attainable goals (even if in stages and phases) accompanied by the economic strength that could fund and sustain those dreams.

Soviet, American experiences

Post-War global history has shown that no nation in the world had become a global power without having a secure and peaceful neighbourhood, and a strong and supportive manufacturing base. The failed Soviet experience would show that jack-booting the neighbour into submission comes with an extended cost, which proved too costly in this case. The parallel American experience of 'buying' loyalty and sharing prosperity through meaningful means (down to the continuing large-scale illegal Mexican migration) has ensured that no visible State-sponsored threat exists for the US to bother about in its relatively isolated locale after 'Pearl Harbour' and 'Cuban missile crisis'. Embarrassed as the US was, it has since smoked out the Al Qaeda attacks on the 'homeland' with a strong message across the world and continents for recalcitrant elements not to meddle with America.

India does not enjoy such luxury or capacity, and is not expected to acquire at least the latter in the foreseeable future even if it manages to put neigbourhood relations (even barring those with China and Pakistan) on an even keel without further loss of time. A nation that continues to import night-vision thermal-imaging equipment for its battle-tanks, and has spend billions in scarce foreign exchange on recouping and re-equipping its war-machinery has a long way to go, both in terms of inherent military strength and economic strength, what with the diversion of huge sums over a relatively short period for defence procurement taking the bottom out of the nation's economy over issues of national pride and preparedness - for an un-fought war, after all.

At a time when Indian big businesses are investing huge sums overseas, on captive coal-fields and manufacturing facilities, New Delhi needs to ask itself what is needed to make them invest in India, and minimise the nation's dependence on FDI, which experience has shown is anyway hard in coming, particularly in the core and manufacturing sectors. What is more, India has to be as much apprehensive of its friends as it has to be of its known adversaries. After all, it is a larger game of global dominance, played out over the longer term in which India is caught in. How it positions itself and plays it game and part alike, and how and where it travels from there is the question it should ask itself. It is as much about strategy as about tactics, short, medium and long-terms, after all.

By Special Arrangement with : Observer Research Foundation (www.orfonline.org)